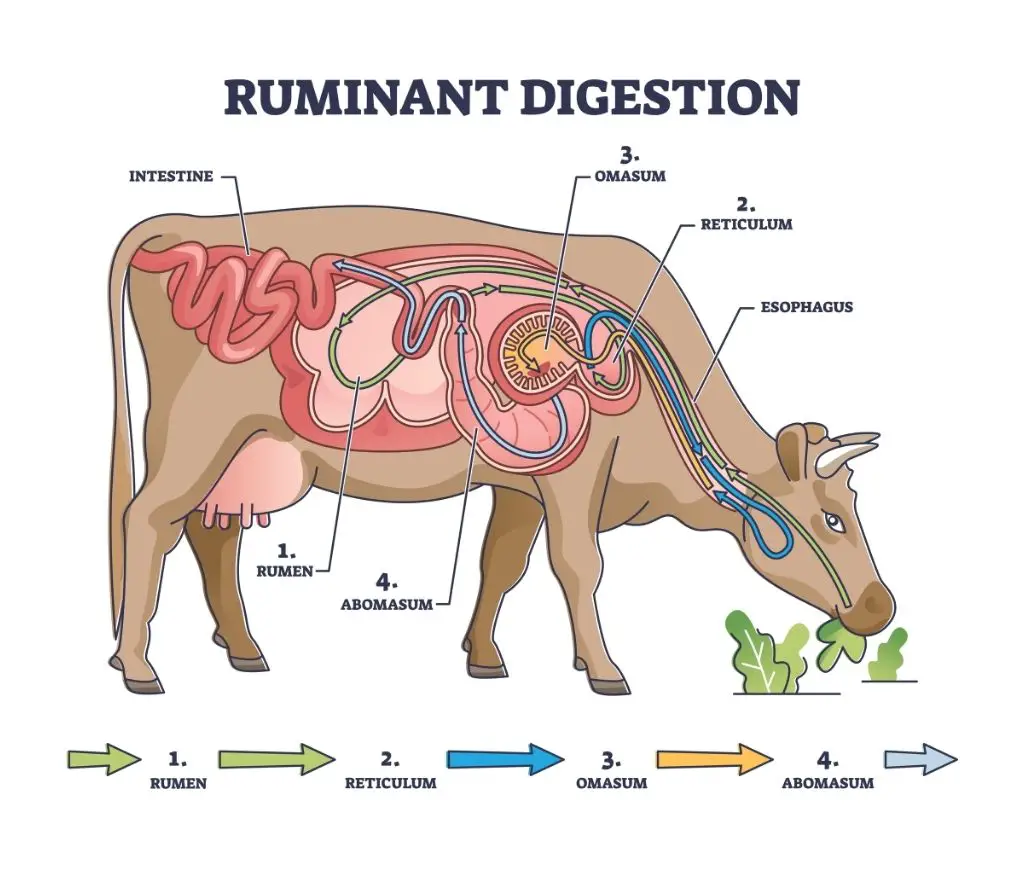

A cow’s digestive system consists of the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small and large intestine. These organs help cows to break down food for the provision of energy.

The main distinctive feature of a cow’s digestive system is its stomach which has four compartments that carry out specific functions. This is different from animals with a singular stomach compartment for digestion known as the monogastric digestive system.

The four compartments of a cow’s stomach are specially adapted to:

- Store and ferment chewed plant material and grain

- Digest cellulose from plant cell membranes

- Synthesize proteins and vitamins

- Absorb nutrients

The main difference between the cow and human digestive systems is that humans have a monogastric stomach while cows have a 4-compartment stomach. A cow’s digestive system is longer than that of human beings because more time is needed to digest plant material.

Table of Contents

Parts of a Cow’s Digestion System

Mouth

The digestion process kicks off in the mouth where the cow uses the tongue, lower jaw incisors, and the upper dental pad to cut foliage from the ground. The molars and premolars grind the plant material further and break it into small digestible pieces during the initial chewing.

The chewing process stimulates saliva production which mixes with the plant material to perform the following functions:

- Contains enzymes that break down fats and starch

- Recycle nitrogen into the rumen

- Prepares the food bolus by assembling the formed food particles

- Buffers the PH levels in the rumen and reticulum compartments of the stomach

A mature cow can produce 50 or more quarts of saliva per day. Saliva production varies in different cows depending on how much time is spent chewing.

Esophagus

The esophagus is a muscular tube that connects the cow’s mouth to the stomach. The esophagus of ruminant animals functions bi-directionally. This means it can move the chewed food from the mouth to the stomach (peristalsis) and back from the stomach to the mouth (antiperistalsis).

The bidirectional movement of the esophagus is enabled by a series of strong wave-like muscle contractions and pressure differences.

The esophagus plays an important role in the rumination process. The previously consumed feed is regurgitated back to the mouth through the esophagus for further chewing and grinding.

Once the cud is chewed thoroughly and broken into small digestible particles, it is swallowed again back into the rumen.

Stomach

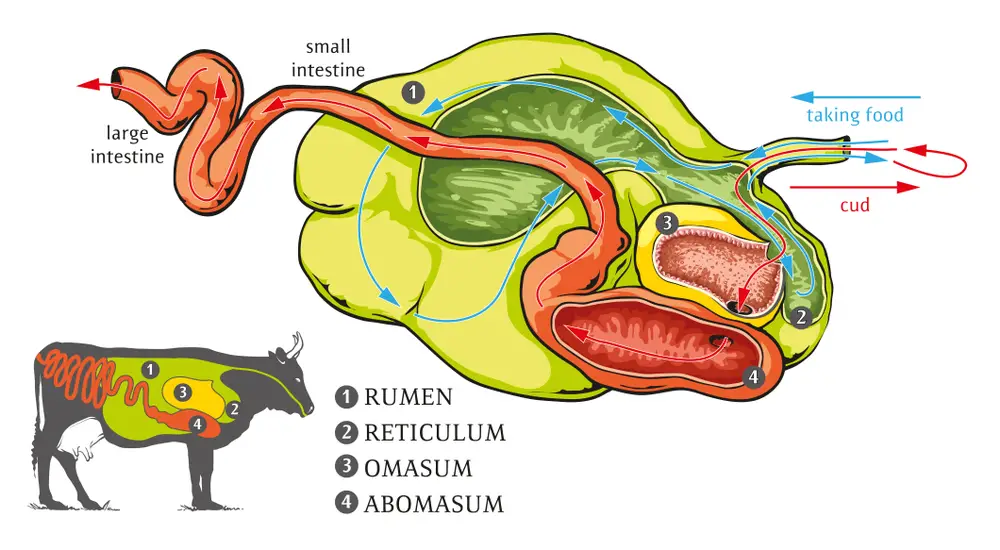

The cow’s stomach is composed of 4 compartments: the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum. The rumen and the reticulum form the reticulorumen, which has microorganisms including fungi, protozoa, and bacteria.

The rumen is the largest of the 4 compartments and holds up to 40 gallons. The reticulum can hold 5 gallons in a mature cow.

A cow’s stomach occupies approximately 75% of the abdominal cavity.

The rumen is lined on the inside with papillae that increase the surface area for greater nutrient absorption. Its large space also creates a vacuum for the fermentation of feed to occur.

The reticulum is also called the ‘honeycomb’ because of its inner lining. It assimilates smaller digested feed particles and moves them into the omasum while the larger particles are retained in the rumen for further digestion.

The inside of the omasum is lined with folds resembling the pages of a book.

Food’s chemical breakdown occurs in the abomasum or ‘true stomach.’ The abomasum secretes hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes that are used to break down proteins and fats. The proteins and fats are then absorbed in the intestines.

Small Intestine

The small intestine of a cow is a 150-feet long tube with a 20-gallon capacity and comprises the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum parts.

In the duodenum, the partially digested matter from the stomach is mixed with enzymes from the pancreas and bile from the gall bladder to assist in digestion.

The jejunum is lined with small, finger-like projections known as villi which increase the surface area for nutrient absorption.

The ileum absorbs any final nutrients that pass the jejunum, bile acids, and vitamin B12.

Cecum

The cecum is a 3-foot long pouch with a 2-gallon capacity located between the small and the large intestine.

Large Intestine

The large intestine is large in diameter but smaller in length. It absorbs water into the bloodstream from the materials passing through it and eliminates any undigested or unabsorbed food in form of fecal matter.

Ruminant Animals Digestion System Development

When a calf is born, it is considered to be a pre-ruminant. Its ruminant stomach is structured but only the abomasum is fully developed and the rumen is significantly smaller.

The calf’s abomasum makes up nearly 70% of the digestive tract. All the digestive metabolic processes happen at the abomasum. At this point, the calf depends on milk which is an easily digestible source of protein and carbohydrates.

The act of suckling by the calf stimulates the development of a fold of muscles in the rumen walls called the oesophageal groove. During suckling, the oesophageal groove delivers the milk directly to the abomasum, bypassing the rumen, reticulum, and omasum.

A fully developed rumen is crucial for the successful weaning process and good growth of the calf. Let’s look at five key ingredients that are required to initiate the development of rumen.

Bacteria

Bacteria are introduced to a calf’s rumen when a calf begins to feed on calf starter concentrates. Bacteria are important in the digestion process.

The carbohydrates in the calf starter are fermented by rumen microbes to produce Volatile Fatty Acids (VFAs) which are propionic and butyric acids. Digestion of forage results in an end product called acetic acid, also a VFA.

Propionic and acetic acids are absorbed into the rumen wall to be converted into metabolites which the calf uses as energy resources. Butyric acid is converted into an energy source to be used by cells in the rumen walls.

Liquid In The Rumen

Liquid in the rumen together with the absence of oxygen provides an ideal environment for rapid bacterial growth.

From 3 days of age, the calf should have unlimited access to clean fresh water to increase its weight gain, promote starter intake, and reduce chances of scouring.

Muscular Movement

Development of rumen activities like contractions, pressure, and regurgitation is necessary to enable the mixture of feed and outflow of materials from the rumen.

Muscular activity in the calf’s rumen is initiated by increased dry feed intake. When the calf is fed milk, hay, and a starter shortly after birth, muscular contractions begin to occur as early as three weeks of age.

Absorptive Ability Of Tissue

Epithelial tissue in the rumen is responsible for the absorption of volatile fatty acids. When a calf is born, the epithelial tissue does not have the ability to absorb.

Fermentation of starter feedstuff in the rumen enables the production and subsequent absorption of volatile fatty acids. This in turn stimulates the development of the epithelium into finger-like projections called papillae to increase its surface area for absorption.

Availability Of Feedstuff In The Rumen

Dry feed intake plays a very important role in the calf’s rumen development. Fermentation of concentrates to propionate and butyrate encourages early rumen development.

Clean, fresh starter is offered to the calf at three days of age The starter should be highly palatable and should meet the nutrient recommendation.