DNA recovered from the Near East suggests that all cattle can trace their heritage back to 80 oxen domesticated about 10,500 years ago in present-day Syria and Turkey. Several bovine species have been subject to domestication, but taurine cattle (Bos taurus) and zebu (Bos indicus) form the ancestry of almost all cattle.

These species derive from the auroch, common throughout most of North Africa, Europe, and Asia, and the once green Sahara at the end of the last glacial period 12,000 BP (Before Present).

Table of Contents

The History of Cattle

A study was conducted by scientists from the French Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), the National Museum of Natural History in France, the University of Mainz in Germany, and the University College London. They extracted the DNA from the bones of domestic cattle excavated from Neolithic to Iron Age archaeological sites in the Levant, Western Iran, and Central Anatolia. These sites date back to the beginning of farming and are the first examples of cattle domestication.

The DNA sequences from these ancient cattle and their modern-day relatives were subjected to Bayesian analysis via computerized simulation. This process revealed minor differences, which could only have occurred if a small number of the cattle, approximately 80 in this case, had been domesticated wild oxen or aurochs (Bos primigenius).

The Southwest Asian subspecies Bos primigenius primigenius Asia was the ancestor of all taurine cattle, and Bos primigenius namadicus from India was the originator of zebu cattle. The Brahman breed (also known as Brahma) is descended from the Bos indicus species, known as the sacred cow of India.

Doctor Ruth Bollongino of CNRS and Mainz University and study leader stated that obtaining trustworthy genome sequences from remains discovered in colder climates is relatively easy. This explains why mammoths are among the first extinct creatures to provide accessible DNA.

However, warmer temperatures deteriorate DNA and make accurate readings more challenging to gather. They had to be sure the genetic material they were examining was from the original aurochs, not cattle that had existed afterward.

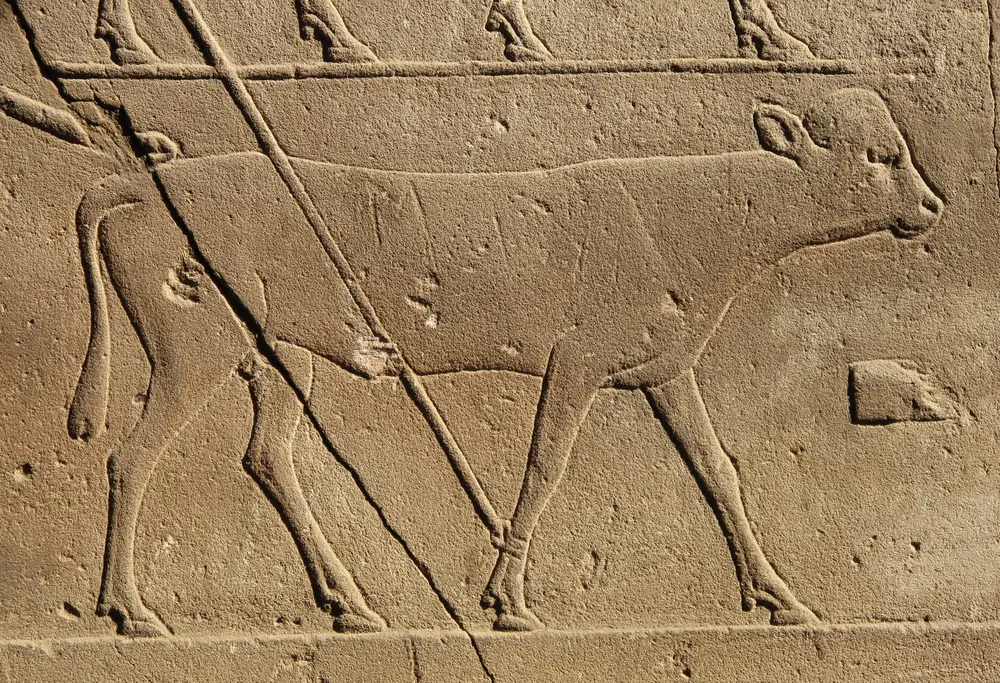

Rock Engravings

The number of animals discovered significantly affects archaeological studies of cattle domestication. We know from uncovered remains that these ancestors of modern cattle were commonplace in Europe and Asia around 12,000 years ago. There are also rock engravings of African cattle showing a captured wild auroch bull dating back to around 6,000 years ago.

Professor Joachim Burger, also based at the University of Mainz, stated that wild aurochs differed significantly from modern domestic cattle. They were huge and fierce, lacking the domestic or docile characteristics we are familiar with today.

Consequently, capturing these animals and their subsequent handling and breeding would not have been easy. It would have taken generations of special breeding for more docile behavior and smaller sizes to become commonplace.

Archaeological data suggests the domestication of taurine cattle started about 10,500 years ago on the western part of the border between Turkey and Syria, in the area known as the Fertile Crescent. Ancient African cattle also originated in this area of the Middle East.

The first domesticated zebu appeared in the Indus Valley on the edge of the Indian Desert around 2,000 years later. Taurine cattle first arrived in China about 5,000 years ago.

The oldest indications of European domesticated cattle are some bones dated 8,500 BP found in Thessaly, Greece. Remains of early European farms suggest there were two principal migration routes for the movement of livestock: along the river Danube and the Mediterranean coastline.

Ancient Ceramic Pottery

Isotopic analysis of ancient ceramic pottery has revealed traces of bovine dairy fat products, confirming milking of domesticated cattle was already underway around 6,000 years ago in the British Isles and 7,500 years ago in northern Europe.

Although the numbers of zebu cattle are roughly the same as taurine at 800 million, zebu distribution is less widespread and concentrated around areas with a similar climate to the original domestication sites in the Indus Valley.

However, there is evidence of westerly zebu migration after the excavation of humped bull figurines in Iraq, dated 6,500 BP, and Sumerian vase fragments dating back to 4,750 BP. Yak domestication first happened at about 4,500 BP in Tibet and its surrounding regions.

Longer horns are helpful for wild cattle as they repel predators and mating rivals. Domestically, however, they complicate animal handling and can cause injury when cattle group together. The first instances of polled or short horn taurine cattle were in Mesopotamia during the early Bronze age, from 2,580 to 5,100 BP.

Cattle sizes have become progressively smaller since the end of the Bronze Age, probably due to continuous adjustment to domestication and the scarcity of food in areas with colder winters.

The major European empires of Greece and Rome used cattle for draft purposes. The Greeks also involved them in sacrifices and milking. The Romans didn’t use them as dairy cows, possibly due to the low prevalence of a human lactose tolerance allele in Mediterranean populations.

Heavy Plows

The arrival of heavy plows allowed the usage of areas of previously unworkable heavy clay soils and started an agricultural revolution around 1000 to 1300 AD. Cattle were used as draft animals for plowing but were superseded by horses, especially after the widespread introduction of the horse collar in about 1000 AD.

Although the agricultural revolution caused human populations to rise, this growth was countered, first, by the crop failures that caused the Great Famine of 1315 to 1317 and, second, by the Black Death from 1346 to 1351. The Great Famine reduced the population of Northern Europe by around 20 percent and the Black Death by over 30 percent. Cultivation ground to an almost complete halt, but cattle keeping became more common.

It didn’t take long for human and livestock populations to recover. The introduction of pasture enclosures, animal feed cultivation, and improved storage methods improved the survival of larger animals during the winter. Breeders also began using sire selection to enhance the quality of their herds.

The prices of dairy products soared in the mid-16th century as the fine milk-producing reputation of cows from the north of the Netherlands became widespread.

Demand for Beef

Demands for beef became so high in the booming cities that local farms struggled to cope, and settlements started to rely on “drovers” who delivered herds of cattle on the hoof from areas where extensive farming was viable.

Droving continued throughout Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries. The drovers took beef cattle reared on Scottish pastures to London, and tens of thousands of cattle a year were driven from Hungary to the cities of Venice, Strasbourg, and Vienna in the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries.

Western-European cattle husbandry improved towards the 18th century, and urban farms were able to satisfy demand with supply. However, the higher densities of animals facilitated outbreaks of cattle plague originating in Hungary.

The industrial revolution of 1760 caused an even greater demand for agricultural products as urbanization increased. The British Agricultural Revolution led to significant innovations in cattle husbandry with the further sophistication of sire selection and pedigree documentation. Early cattle herd books led to the evolution of the Swiss Braunvieh breed, for example.

These methods saw the introduction of several landmark British breeds of cattle. The successes of the Shorthorns and Longhorns preceded the development of the Hereford and Aberdeen Angus beef breeds and the dairy Ayrshire.

Distribution Via Agricultural Exhibitions

The movement of sires from central and western Europe to eastern regions directly resulted from newly-introduced 19th-century international agricultural exhibitions. Cattle once bred for draft purposes were now converted to dairy production in the Northwestern European Lowlands and Scandinavia. Several beef breeds were introduced in France. The Charolais was registered in 1842 and the Limousin 10 years later.

As the 20th century progressed, breed formation changed the face of milk and meat production in cattle. Herds became uniform in their breeds, and high-performing breeds moved beyond their areas of origin and were exported to different countries and continents. Less successful species fell in numbers or completely disappeared.

How Did Cattle Get To The US?

When the conquistadores arrived in the Americas from Spain in 1492, the “New World” became available to European cattle. Christopher Columbus shipped cattle to the Caribbean island of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) on his second voyage in 1493. Every Spanish vessel over the next 50 years took five heads of cattle with them. Although only two or three survived, these animals formed the basis for cattle farming in many areas of North and South America.

Cattle arrived in Mexico in 1521, and 20 years later, the first herd of 500 cattle crossed the Río Grande as “meat on the hoof” for the Spanish explorers in Texas. These cattle were the ancestors of the modern-day Texas Longhorn, the first beef-producing cow in North America. In 1524, the first of many Spanish cattle to go directly to South America landed at Santa Marta, Colombia.

The First European Arrivals

The descendants of the modern Canadienne cattle were among the first to come to North America. They originated from the French areas of Normandy and Brittany and arrived a year after English colonists arrived in 1607. The first documented occurrence of English cattle in North America was in Virginia in 1609. The Netherlands was the first to introduce dairy cattle.

Consequently, by the end of the 18th century, North America’s cattle population comprised a mixture of cattle from the Iberian Peninsula and Northern Europe. The Texas Longhorn could not satisfy the increasing demands for beef and dairy products, so the British Shorthorn was introduced in 1783 to resolve the shortfall.

With time, the Angus has superseded the Hereford and Beef Shorthorn as the most popular breed for beef in Canada and the United States. However, the Beef Shorthorn is still prevalent in Australia and Argentina.

The exotic cattle boom of 1967 transformed the North American beef cattle industry. It started in Canada when large numbers of beef breeds arrived from mainland Europe, such as Charolais, Simmental, Limousin, and Gelbvieh. These breeds have a faster growth rate and produce leaner meat than Angus and Herefords, although records show they still lag behind in registrations.

Several zebus were shipped to Brazil from Malabar, India, in 1813; the first ones arrived in North America in the 1840s.

How Did Cattle Get To Australia and NZ?

The first cattle imports to Australia happened in a similar way to North America. The first breeds to arrive were Zebus from India towards the end of the 18th century before the 19th century saw the arrival of mainly British breeds and Dutch Friesians and Holsteins.

In 1896, cattle tick-borne diseases decimated beef-cattle productivity, particularly those of British origin. The problem was solved by crossbreeding with Indian and American zebu cattle, which were much more disease resistant. This method rescued the beef cattle industry in Australia.

New Zealand did not adopt the zebu and only has cattle of European descent, mainly of British and Dutch origins. An estimated 36 percent of the country’s dairy cattle are Jersey and Holstein crossbreeds.